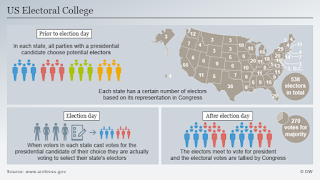

One consequence of the 2016 Presidential election has been calls for abolishing the Electoral College. Hillary Clinton received 2.8 million more votes than Donald Trump, but lost the Electoral College, 304-227. About 107,000 votes in Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Michigan gave Trump his victory.

| |||

| Trump vs Clinton 2016 Presidential Election |

Massachusetts Senator and 2020 Democratic hopeful Elizabeth Warren now leads the charge for dropping

the Electoral College. She, and others, see it as an undemocratic anachronism that violates the principle of one-person-one vote and unfairly blocks popular will. Conservatives (some support it only because it helped the Republican nominee last time) argue eliminating it will diminish the importance of small states and rural areas while unfairly advantaging big cities.

A Little History

The Electoral College resulted from compromises in drafting the constitution. The framers preferred letting electors choose the President, fearing demagogues would unduly influence uninformed, uneducated voters. They sought a balance between popular will and the risk of a tyranny of the majority. States with large populations might have outsized sway if the popular vote elected the President. The drafters discarded the alternative of letting Congress pick the President in favor of the Electoral College.

The popular vote winner usually has also won the Electoral College. The 2016 result represented only the fifth time a candidate who didn’t win the popular vote captured the White House. It happened, of course, most recently before 2016 in 2000 when Al Gore won the popular vote, but lost the Presidency to George W. Bush in the Florida debacle.

The Debate

Fear of harming small states now stands as the principal argument for keeping the Electoral College. Supporters say candidates would focus nearly all their attention on big cities like New York, Chicago,

Los Angeles, and Houston, not thinly populated rural states in the South and Rocky Mountain West. Wyoming, with a population of 577,000, has become the poster child for keeping the Electoral College. No Presidential candidate would pay it any attention, the story goes, if the country abolishes the Electoral College.

Fear of third parties also now gets raised as a reason

for keeping the Electoral College. Former Reagan administration official Peter Wallison contends America runs the risk of spawning a multitude of minor parties with strong, single issue focus, any one of which could elect a President in a three, four, or five party race in which the winner would only need a plurality of the popular vote. In his nightmare scenario, we’d require a run-off system or we’d face the prospect of coalition governments now seen in parliamentary systems.

Those advocating change focus on the unfairness of the Electoral College. In a democracy, getting the most votes should translate into winning office. The popular will should prevail and protecting small state or rural state interests, while important, shouldn’t become the tail wagging the dog. In a system predicated on majority rule, this principle carries a great deal of weight.

A better view

Persuasive as the pure democracy rationale is, a better argument for abolishing the Electoral College may lie in the fact it doesn’t do what its supporters say it does. It doesn’t protect small state and rural state interests because candidates ignore those states in Presidential elections anyway. Voters in small states and rural areas might get more attention in a popular vote system than they do now. Presently, having a divided electorate, as measured by partisan affiliation, determines where candidates put their emphasis, not size or rural/urban status.

In 2016, two-thirds of all general election campaign

events occurred in six states – Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Florida, Virginia, Ohio, and Michigan. The nine smallest states received zero attention as measured by candidate appearances. Big states didn’t fare better. California, New York, and Texas hosted three campaign events between them. Why? Only the “swing states” mattered. It wasn’t rural/urban status or size that determined where the candidates campaigned. They appeared where people hadn’t made up their minds. Neither Clinton nor Trump needed time in California (a cinch for Clinton) or Idaho (locked up for Trump).

Now, rural voters in New York and California (both states have plenty) get ignored, as do urban voters in Memphis and Atlanta. If every vote mattered, Republicans might see the value of appealing to blacks and browns in Seattle, Chicago, and New York. Democrats might find risky blowing off white farmers and small town dwellers in Tennessee, South Carolina, and Nebraska.

The Electoral College is part of our history. As one advocate for keeping it wrote, “a deal is a deal.” But, the reasons for changing it now outpace the value in keeping it.

Eliminating the electoral college probably means a constitutional amendment -- a two-thirds vote in both houses of Congress and ratification by 38 states or calling a constitutional convention, which requires 34 states and has never happened. Twelve states, all controlled by Democrats except one swing state, have signed the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact in which they pledge they will vote electors for the national popular vote winner if states controlling 270 or more electoral votes agree they’ll do the same. All routes to constitutional change seem unlikely now, given the political dynamics.

Who currently benefits shouldn’t determine this issue. As journalist Ryan Cooper put it, “if a Democrat ever wins the presidency while losing the popular vote, it’s a safe bet the Electoral College will be gone in about five minutes.” That’s not how a democracy should operate. Principle should dictate this decision. Increasingly, it appears principle dictates ditching the Electoral College.

No comments:

Post a Comment